---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THIS ARTICLE WAS PUBLISHED IN NEW YORK TIMES ,Just 30 days back to Maharaja death .

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

November 26, 2000

A Maharajah's Festival for Body and Soul

By RICHARD SCHECHNER, a professor of performance studies at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, is working on a book about Indian theater and ritual.

RAMNAGAR, India A KING, his prince and his courtiers ride in full pomp atop richly caparisoned elephants. They, along with tens of thousands of spectator-devotees, their hands pressed together in the Hindu prayer-salute, admire and worship the gods Vishnu and Lakshmi in their incarnations as Rama and Sita. Titanic battles pit human-size gods against 50-foot-high demons.

For a whole month there is continuous theater, 31 daily episodes of love, war, exile, intrigue and adventure. The stages for this performance of great magnitude are locations dispersed, filmlike, throughout Ramnagar (literally, Ramatown), a midsize settlement across the Ganges River from the holy city of Benares in the north Indian province of Uttar Pradesh.

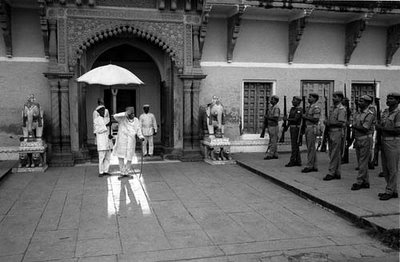

Ramnagar is the seat of the Maharajah of Benares, Vibhuti Narain Singh, still revered by multitudes of Indians more than 50 years after losing his crown and his kingdom when the Princely State of Benares was dissolved into the Union of India in 1949.

This is Ramlila, or Rama's play: participatory environmental theater on a grand scale. Ramlila is theater — and it is religious devotion, pilgrimage, a festive fair and political action. Audiences range from a few thousand for some episodes to 100,000 for others. Every Hindu Indian, and most Muslims, know the story of Ramlila; it is always being presented in films, on television, as graphic art and in literature, ranging from great poetry to comic books. There are thousands of local Ramlilas enacted all over Hindi-speaking India — and in the diaspora, too, from Trinidad to Queens.

But the Ramlila of Ramnagar is different. It features the Maharajah of Benares as patron, director and player. It is many days longer than other Ramlilas. It is more skillfully produced theatrically. It draws much larger and more devoted crowds. And its future may be more precarious.

During Ramlila, Ramnagar is transformed into a living theatrical model of the entire Indian subcontinent, from the Himalayan mountains in the north to Sri Lanka off the southeast coast. Nothing of Ramlila's size, totality and intensity has been seen in the West since medieval times. Compared with Ramlila, the Oberammergau Passion Play and Peter Brook's "Mahabharata" are small scale.

Like all great art, Ramlila changes its meaning over time. Nationalist sentiments, present mostly as a vague background 25 years ago, now operate openly, especially among many younger male spectators. And today's Hindu nationalists, wanting to turn India into a Hindu state, hold Ramraj up as their ideal.

Under the watchful eye of the Maharajahs of Benares, Ramlila has been performed in Ramnagar every year since the early 1800's. But how long it will continue is no longer certain. The pressures of India's ever-increasing population and the nation's vigorous economic growth threaten this unique theatrical-religious cycle.

Ramlila needs lots of time and space — scarce in today's India. People who once would support Rama in his war against Ravana now run businesses that can't be ignored for a month. At the same time, forests, ponds and open sites are being eaten up by housing and highways. Even finding younger actors and technicians to replace those already well past retirement age is proving difficult.

As an American theater director who has studied Ramlila since 1976, I am fascinated by its scale, by the attention to detail in its staging, lighting, scenic design and costuming, by the acting and singing, and by the convergence of narrative, spectacle, devotion and politics. I have seen all 31 episodes twice and, along the way, interviewed the Maharajah, the Rajkumar (crown prince) and many participants and performers in the play, as well as a number of spectators. In September, I went to Ramnagar to see portions of this year's spectacle, as I have in other years.

Ramayana means Rama's journey, and Ramlila suggests this journey literally. There are no seats. People sit on the ground, stand, watch from rooftops or perch on walls. When the action calls for it, the crowd moves from one location to another. Following in Rama's footsteps is fundamental to Ramlila. This movement is a kind of pilgrimage, a worship-in-action.

The festival itself transforms an area of many square miles. Some of the stages are enclosures in the middle of the town, others are deep in what was once forest and jungle, or on grassy hillsides and in open fields, or amid large gardens of fragrant blooming trees and temples and marble gazebos built by former maharajahs. For one scene, the stage is the Maharajah's own palace, known as the Fort, which it really once was.

Each episode is called a lila. On most days, Ramlila begins at 5 p.m. and continues until 10 at night. Some episodes last late into the evening and one, Rama's coronation, does not end until dawn.

The staging is simple and iconographic, replicating images from temples, religious paintings and popular posters. The costumes are richly woven silks in resplendent gold and red. The faces of some actors are adorned with glittering jewels. Many colorful masks and large, brightly painted papier-mâché effigies animate the performances.

But this tradition is no longer secure, though it has persevered for more than 100 years. Kaushal said he did not want his son to portray Ravana. "Life as a farmer is too hard," he said. "The Maharajah has no money anymore. I want my son to work in the city." The sentiment is heard frequently these days.

The original Ramayana poem itself is never spoken because Sanskrit is a language very few Indians understand. Instead, what people hear is the Ramcharitmanas, a 16th-century Hindi version of the epic. The entire Manas, as it is called, is chanted by 12 men sitting each night in a circle close to the Maharajah. But even though at Ramlila one can see dozens of people reading texts of the Manas, many others cannot understand its archaic Hindi. To enable everyone to follow the story, a maharajah in the mid-19th century, Ishwari Prasad Narain Singh, commissioned a group of poets and scholars to compose dialogue in vernacular Hindi for the Ramlila.

First, the Maharajah ritually worships weapons and horses — the symbols of his royal power. Next, he and his court mount magnificently adorned elephants and parade through the adoring crowd from the Fort to Lanka. The Maharajah then proceeds through the battleground and departs. "It is not proper for one king to witness the death of another," the Maharajah told me. "Therefore, I do not stay to watch this lila."

One group that always gains maximum pleasure and devotion from Ramlila are the sadhus, holy men who have renounced worldly goods, live on alms and spend their days and nights singing praises to the gods. The Maharajah provides all sadhus with daily rations of rice and lodging. But despite this generosity, there are many fewer sadhus than before. "Who wants to renounce the world these days?" a man asked me.

And where there used to be lightly traveled paths leading into the quiet countryside, now there are streets clogged with diesel fume spewing trucks and buses, horn- blasting cars and motorcycles, not to mention bicycles, cows, water buffalo and goats. The deeply rutted dirt roads have not been filled or smoothed for years.

Why is the Ramlila so enormous? The most direct answer is that since the early 19th century, the Ramlila has been the defining project of the Maharajahs of Benares. The current line was established in the mid- 18th century and, caught between a failing Mughal power and an emergent British presence, was not secure on the throne. Sponsoring a large Ramlila was the way for the Maharajahs of Benares to shore up their religious and cultural authority at a time when they were losing both military power and economic autonomy.

Vibhuti Narain Singh ascended the throne in 1939 when he was a boy of 12. Ten years later, his kingdom was dissolved. But the Maharajah continued to rule, not in political fact but by virtue of his learning, his religious devotion and his patronage of Ramlila. Wherever he goes, people greet him with ringing shouts of "Hara! Hara! Mahadev!" ("Shiva! Shiva! Great God!"), because he is believed to be a manifestation of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and reproduction. Now 73 and frail, unable to walk unassisted, the Maharajah is doing all he can to pass the Ramlila on unchanged.

With the participation of Nissar Allana, a stage designer, and myself, the Maharajah is planning a Ramlila museum, which will take shape first as an Internet site with thousands of images, as well as sound recordings and scholarly and historical materials. Kapila Vatsyayan, one of India's leading performance scholars, hopes to edit a facsimile edition of an early-19th-century illuminated manuscript, a four-volume version of the Manas with hundreds of original illustrations in a style influenced by Mughal painting.

I am helping to prepare a prompt book detailing all of the current staging — a how- to-do-it manual that the Maharajah hopes will assist his son, Anant Narain Singh, who is now in his 30's, when it becomes his turn to oversee the Ramlila.

The Ramnagar Ramlila has thrived for nearly two centuries as a magnificent spectacle, a religious experience and a cosmic drama. But will it make it through the next 25 years? The crown prince has never known what it is to rule a state. Is his devotion as intense as his father's? Can he command the same respect? He is a more modern man than his father. Is it an irony or a sign of the times that on several occasions when we have met, I was dressed in Indian kurta and pajamas, while he wore casual Western clothes?

Meanwhile, money is a big problem. Environments and costumes are beginning to look rundown. Performers receive a few hundred rupees as a contribution to those who do sacred work. At one time, this money amounted to something, but no longer. Atmaram, the 80-year-old supervisor of props, sets, lights, costumes and special effects, was not sanguine about the future. "I am training no one," he said. "After I am gone, who will know what to do?" Atmaram has been on the job for more than 50 years. The knowledge he carries in his head is not replaceable.

Until now, few outsiders have attended Ramlila. It doesn't make sense to go for one day, and Ramnagar does not have the infrastructure to accommodate longer visits, unless one is ready to rough it. For more foreigners to come — or even for upscale Indians from Delhi and Calcutta — Ramnagar will require extensive upgrading. The crown prince is studying the possibility of converting a portion of the Fort into a five- star hotel.

Yet everyone recognizes that Ramlila's uniqueness is a function of its nontourist Indianness, of its being theater and more than theater at the same time. Will increased attention from outsiders help preserve or further disturb Ramlila?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Although , I teach Technology and Management but HISTORY always fascinate me . i just delight whenever i see my forefathrs (Bhumihar Brahmins) were in lead to serve the society or to make society enable.